Quasi-Judicial Authority

Tomorrow we have to make a decision on a proposed settlement of the CoPar litigation. Like the rest of the council, I've spent an enormous amount of time studying this issue and searching for the best course of action. I think if I tried to write about all the aspects of this situation, this would be a very long entry, and I probably would not be done writing it before tomorrow night's meeting.

For whatever it's worth, I did want to spend some time writing about the legal issues of the case, as best as I have been able to understand them.

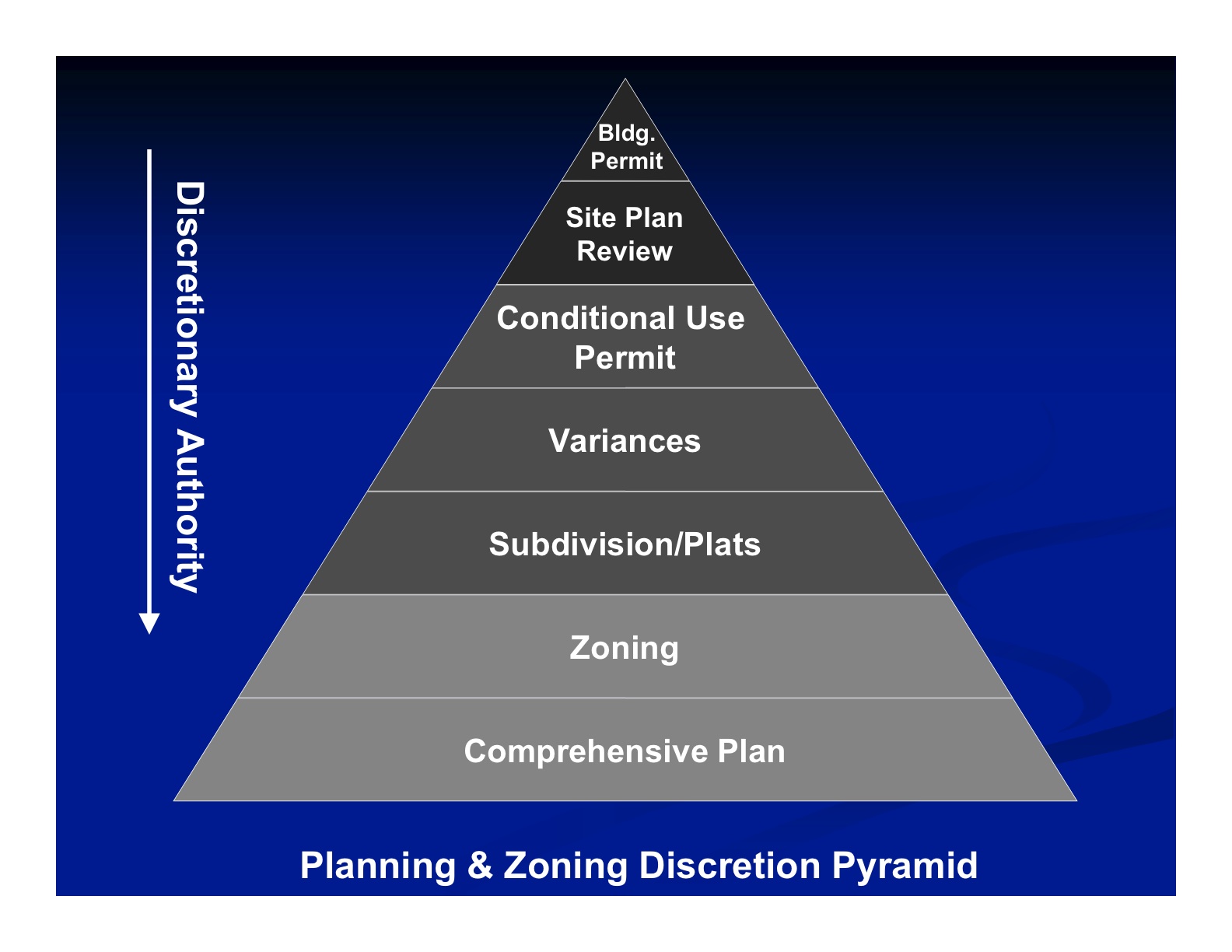

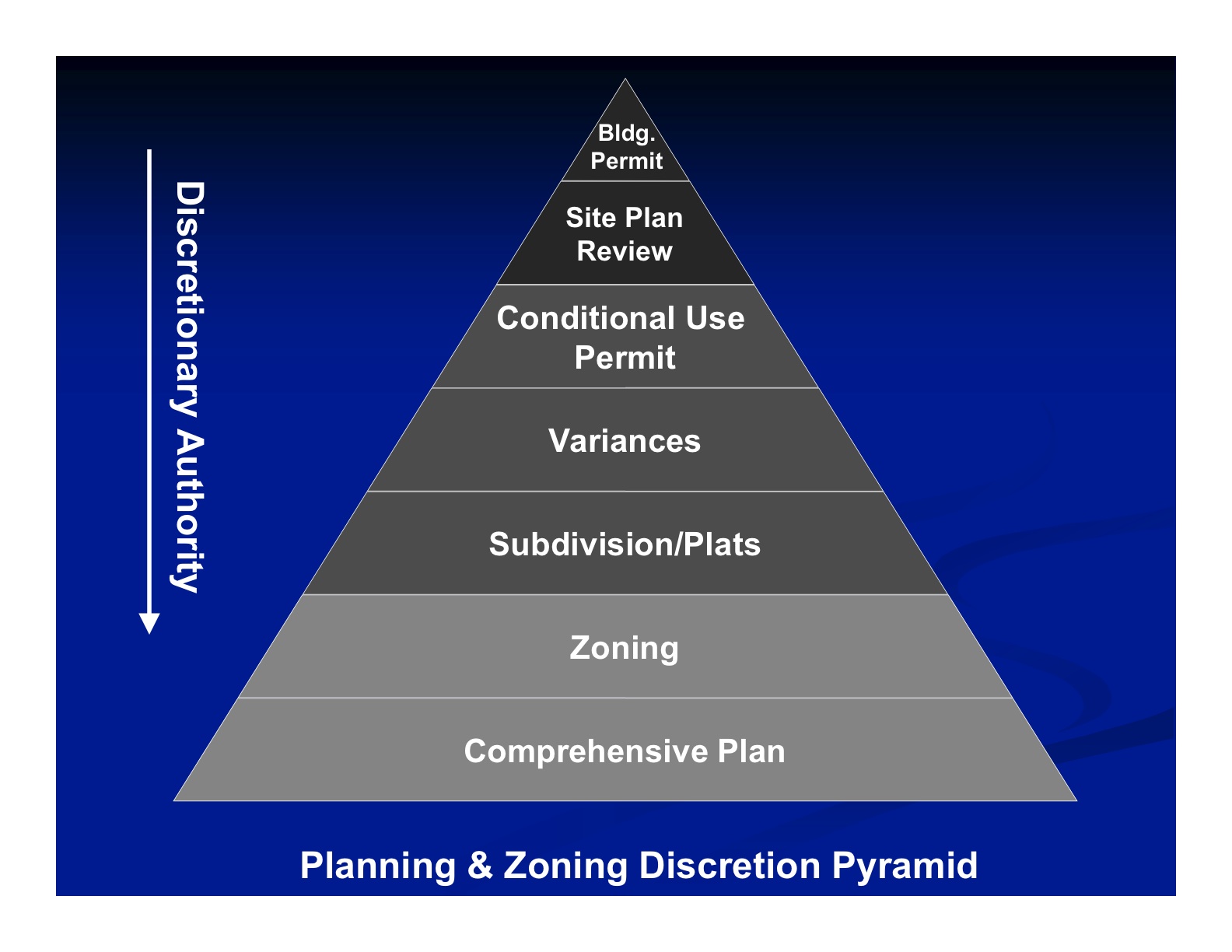

CoPar's application in 2006 was for a conditional use permit. This determined the way that the city council was allowed to evaluate the application. In training seminars sponsored by the League of Minnesota Cities, I've several times encountered the following diagram. (This particular version comes from "Land Use Issues Presentation: Comprehensive Plan and Land Use Ordinances.")

On the bottom of the pyramid, a city council makes broad-brush decisions -- such as the Comp Plan to guide the development of the community over decades to come. When you get to the narrow top of the pyramid, the council has less and less choice; the question is not about what the council would like. Instead, the council must judge what the current law allows given the facts placed before us.

On the bottom of the pyramid, a city council makes broad-brush decisions -- such as the Comp Plan to guide the development of the community over decades to come. When you get to the narrow top of the pyramid, the council has less and less choice; the question is not about what the council would like. Instead, the council must judge what the current law allows given the facts placed before us.

A decision about what to put in the comp plan, or how to zone a property within the parameters permitted by the comp plan, is a legislative decision. According to another League of Minnesota Cities Insurance Trust document ("Zoning Decisions," p. 1),

The LMCIT document also discusses how a judge would review a decision (p. 5).

It should be no surprise that the LMCIT strongly recommends that a city create a written list of findings for quasi-judicial decisions such as those about conditional use permits (p. 6).

For whatever it's worth, I did want to spend some time writing about the legal issues of the case, as best as I have been able to understand them.

CoPar's application in 2006 was for a conditional use permit. This determined the way that the city council was allowed to evaluate the application. In training seminars sponsored by the League of Minnesota Cities, I've several times encountered the following diagram. (This particular version comes from "Land Use Issues Presentation: Comprehensive Plan and Land Use Ordinances.")

On the bottom of the pyramid, a city council makes broad-brush decisions -- such as the Comp Plan to guide the development of the community over decades to come. When you get to the narrow top of the pyramid, the council has less and less choice; the question is not about what the council would like. Instead, the council must judge what the current law allows given the facts placed before us.

On the bottom of the pyramid, a city council makes broad-brush decisions -- such as the Comp Plan to guide the development of the community over decades to come. When you get to the narrow top of the pyramid, the council has less and less choice; the question is not about what the council would like. Instead, the council must judge what the current law allows given the facts placed before us.A decision about what to put in the comp plan, or how to zone a property within the parameters permitted by the comp plan, is a legislative decision. According to another League of Minnesota Cities Insurance Trust document ("Zoning Decisions," p. 1),

When adopting or amending a zoning ordinance, a city council is exercising so-called “legislative” authority. The council is advancing health, safety, and welfare by making rules that apply throughout the entire community. When acting legislatively, the council has broad discretion and will be afforded considerable deference by any reviewing court. City councils are ultimately accountable to the voters for legislative decisions.In contrast, when deciding how to apply the comprehensive plan and the zoning -- for example, by judging whether or not a specific conditional use permit should be issued -- the city council is making a quasi-judicial decision. The same LMCIT document goes on to say, with regard to quasi-judicial authority:

The task is to determine the facts associated with a particular request, and then apply those facts to the legal standards contained in the zoning ordinance and relevant state law. A city council has less discretion when acting quasi-judicially, and a reviewing court will examine whether the city council applied rules already in place to the facts before it. In general, if the facts indicate the applicant meets the relevant legal standard, then they are likely entitled to the approval.The LMCIT document provides more information specific to conditional use permits (p. 3):

City councils sometimes misunderstand the level and the nature of discretion they have when reviewing applications for conditional use permits. If a proposed conditional use satisfies the conditional use standards set forth in the zoning ordinance, then generally the landowner is entitled to the conditional use permit. The city made the legislative decision about the appropriateness of a kind of use in a zoning district when the council adopted the ordinance providing for the use as conditional. When considering a conditional use permit application, the city is tasked with the more limited quasi-judicial role of considering whether the facts of a particular application satisfy the standards set forth in the ordinance.Boiling things down, CoPar's argument is that the city was arbitrary or unreasonable in denying their application, because their proposal (in their view) did comply with the city's standards. In order to appeal the city's decision, they filed suit. If we proceed to court, a judge will examine the record and determine whether the city applied the law correctly to this situation.

The LMCIT document also discusses how a judge would review a decision (p. 5).

If the city action is challenged, courts will review the decision on the public record. The record must demonstrate the city exercised the appropriate level of discretion and applied the relevant standards in a reasonable fashion. It may not matter that the city acted reasonably if the city is unable to prove its actions through the public record. (emphasis added)It is very important to understand the role of the record. The judge can only determine whether or not the decision was appropriate, based on the reasons given by the council when they made the decision. Was the law applied correctly, given the facts set out by the public record when the council's decision was made? If someone, after the decision, came up with an added reason or better explanation for why it was reasonable to turn down the application, that will not help the city win the case.

It should be no surprise that the LMCIT strongly recommends that a city create a written list of findings for quasi-judicial decisions such as those about conditional use permits (p. 6).

The written statement explaining the reasons for the zoning decision is particularly important for quasi-judicial decisions such as variances and conditional use permits. The League recommends the city adopt written findings of fact and conclusions of law whenever a city makes such decisions. The document should identify the relevant legal criteria such as statutory standards or code provisions, explain the relevant facts relating to the particular application, and then apply those facts to the legal criteria. The document should provide a court with everything needed to uphold the zoning decision.Unfortunately, in the decision that led to the current lawsuit, those written findings were never produced. This is just one of the complications that we face, but the unique problems of our specific situation are better saved for a separate article.

Labels: development, process

Post a Comment